Movement, Habit, Learning

Perspectives on the dominance of thumbs and hands in string playing.

As a student at the Royal College of Music I was defeated by a Popper study! It consisted of two

sides of ‘perpetuum mobile’ which I could never play to the end because of a paralysing tension in

my left hand. I eventually consigned that study to the depressing realms of material I would never

conquer. However, about 5 years ago I returned to that Popper study, dusted it down, and found I

could play it right through, at speed, with no difficulty. What had changed? Now I was in my sixties.

Back then I had been in my supple, energetic and brain-retentive early twenties. Was it the wisdom

of age helping my left hand? Was it Feldenkrais magic working its wonders?

A combination of a career’s worth of self observation and the creative thinking which characterises

the Feldenkrais Method was behind this transformation. I was now playing the study without the

interference of a squeezing left thumb. My four fingers could fly around the fingerboard unimpeded

in the same way as I use them when playing the piano. As a teenager I had established my vibrato by

taking my thumb off; I had also discovered that I could increase the stretch of my extension if I

took my thumb off. Here was yet another advantage to liberating my thumb from the cello neck which,

sadly, I only recognised much later in my career.

As a Feldenkrais practitioner I observe string playing through the lens of movement. The thoughts

laid out below are therefore more about movement and function than about instrumental technique. My

perspective is obviously cello-centric. However, I believe that my suggestions can be relevant to

upper strings too. For the sake of clarity there are two sections in my article but the subjects

are profoundly connected.

Thumbs. Help or Hindrance?

If there is unwanted tension in the hand or arm, check the state of the thumb! Is it being a help

or a hindrance?

“more muscles go to the thumb in modern humans than in almost all other primates, reinforcing the

hypothesis that focal thumb movements probably played an important role in human evolution.“ Diogo,

R; Richmond, BG; Wood, B (2012).

We exhort our students to “relax the bow hold,” to “relax the left hand”. But if you simply relax

the whole hand, indiscriminately, it is likely to become too floppy to function usefully.

Evolution provided us with opposing thumbs which love to grip. In my opinion the answer to the

challenge of relaxing both our bow holds and our left hands lies with how we understand and train

our thumbs in order to ween them away from unconscious, habitual, uncalibrated gripping and

squeezing.

Think about pianists. Do they need a thumb pressing from underneath? Obviously not. Pianists use

their thumbs with an equal dexterity and sensitivity to all the other fingers. Thumbs clearly have

the capacity for extraordinary refinement and nimbleness, alongside their instinctive ability to

provide a strong grip.

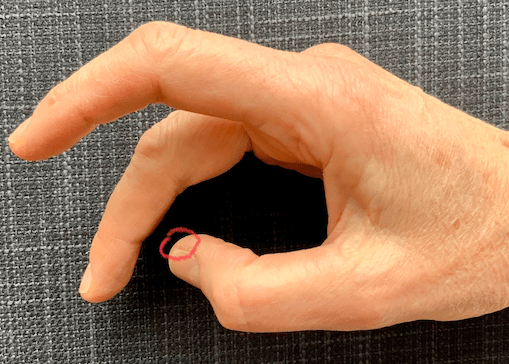

Pianists use their thumbs on the outer edge. I have found that a thumb is less likely to revert to

gripping if it is positioned sideways in relation to the the fingers. Gently maintaining flexion at

both knuckles also helps. The gripping response is more likely to be triggered by turning the

thumb- pad inward towards the fingers (particularly towards the little finger) and by locking the

thumb straight. Therefore, delicately contacting the inner corner of the thumb (close to the nail)

on the frog or on the cello neck, with knuckles softly flexed like skiers’ knees, can be a key to

disrupting the gripping habit. (see photo)

However, hand and finger proportions differ enormously from person to person and double jointedness

can be significant. One blanket solution will not necessarily work for everyone. Therefore, the

over-riding challenge is to educate thumbs to behave with pianist-like dexterity and sensitivity

even when they are positioned in opposition to the four fingers. Addressing this with students I

tend to describe the thumb as a bit of a ‘bully’ because its behaviour is typically mirrored by the

behaviour of the fingers: stiff thumb = stiff fingers. Mirroring can also occur from one thumb to the

other because, fundamentally, our two sides prefer to match rather than to differ. I devise games

and exercises designed to wake up the independence and dexterity in thumbs, and above all to prove

that thumbs do not have to grip to function helpfully. Eventually thumbs can learn to be skilful,

sensitive, and responsive, even when in an opposing role: soft thumb = soft fingers.

In the right hand, a flexible and sensitive thumb will inspire both matching behaviour in the

fingers and also a correspondingly flexible tone in hand and arm, providing encouraging conditions

for balanced, relaxed and easy movement. In the case of the cellist’s left hand, the strength

needed to stop the string can be recruited from the arm, partnered with a pianistic finger action,

bypassing the far weaker and less efficient option of an unconsciously squeezing thumb.

Domineering Hands

You may already be familiar with these somewhat unflattering images. They illustrate the

representation of different parts of the body within the motor cortex (the part of the brain which

plans, executes and monitors voluntary movements), demonstrating that we have proportionally far

more neural connections dedicated to sensing and moving our hands than are dedicated to our arms.

The significant difference between hands and arms in these images supports my own experience. As a

cellist and teacher I have observed that hands tend to dominate, at the expense of arms. If the

images are correct, they depict a setting in the brain which may not be helpful for string players

in every situation. This setting may be an evolutionary predisposition but it is undoubtedly also

the result of many hours of learning and development from infancy to adulthood. Over time we train

our potentially extraordinarily skilful hands for a multitude of tasks, all the while building and

strengthening the network of nerve connections which control these movements. The result of this

wealth of learning is vividly represented in these two images and experienced by us as an

unconscious, habitual preoccupation with, and reliance on, our hands – thereby eclipsing awareness

of the arms.

However, fortunately, what has been learnt can be un-learnt via sensory motor re-education, aka The

Feldenkrais Method.

One of the tenets of the Method is to give small tasks to short muscles, bigger tasks to longer

muscles. Accordingly, long bow strokes will involve more arm focus, whereas short, fast strokes

will function more efficiently if the intention is focussed at the hand. Likewise, in the case of the

left hand, shifts function more efficiently from the arm while it is the finger’s task to stop the

string accurately.

To be clear, it is not a question of either the arm or the hand, it is a question of proportion and

balance, active and passive. The arm is equally capable of small and refined movements, while the

hand may sometimes be required to support with strength. The speed, size and force of the movement

should determine where to direct active intention, where to be relatively passive. When seeking

this balance we need to learn how to circumvent any habitual dominance of the hand where it serves

our purpose less well.

In conclusion, beware the dominance of the hand and its co-conspiritor, the gripping thumb.

Instead, take inspiration from pianists’ nimble thumbs, from the flexibly responsive knees of

skiers (as a model for the bow hold) and from sports like ping-pong, tennis or golf, where the

undoubted importance of the hands is nonetheless balanced by skilful involvement of the arms, and

ideally an appropriate ‘follow through’ response from the whole body.